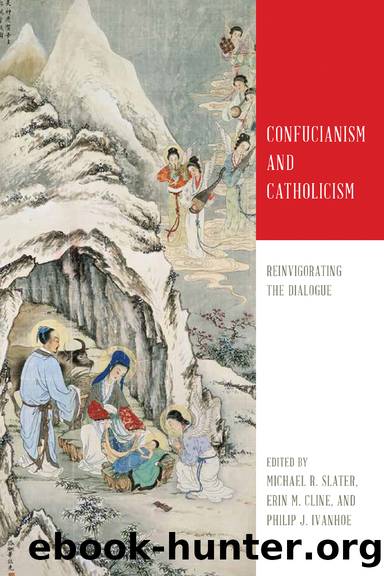

Confucianism and Catholicism by Michael R. Slater

Author:Michael R. Slater

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: University of Notre Dame Press

Published: 2020-03-24T00:00:00+00:00

JOHN CHRYSOSTOM

John Chrysostom’s observation of childish behavior—that children are particularly prone to anger and greed—is similar to that of Augustine, except that, unlike Augustine, he does not seem to notice that children are also jealous. Chrysostom points out that children often show strong appetitive desires for food and toys. Anger, in addition, is particularly apparent in children. For instance, in their tantrums, infants strike the cheeks of those who hold them, flail against their parents’ arms, and even hit themselves. Toddlers may scream, tear their clothes, stamp their feet, or hit each other.59 However, in stark contrast with Augustine, Chrysostom staunchly maintains that children are morally innocent. Chrysostom insists that if children die before growing up, their souls will go directly to heaven, whether or not they are baptized.60 How are we to understand Chrysostom’s apparently contradictory assessments of the moral state of children? How can children at once be sinless and have bad inclinations? To resolve this apparent paradox, we must look at Chrysostom’s conception of sin.

In book 1 of the Confessions, Augustine identifies all kinds of bad tendencies—anger, greed, jealousy, deceitfulness, pride—as sinful, regardless of who display these tendencies. In comparison, Chrysostom maintains that both virtue and vice can be attributed only to agents who have moral choice (proairesis) and free will (gnome).61 Just as we cannot blame people’s natural physical defects, Chrysostom reasons, we cannot hold people accountable for what they do when they are deprived of free choice.62 Since children evidently lack the capacity to freely use their moral choice, they are not culpable for their bad behavior. In a sense, for Chrysostom, children are analogous to those who are mentally disabled. Because they lack the capacity to make a moral choice informed by a full-fledged free will, they cannot be held accountable for their acts.63 Sin, for Chrysostom, is essentially a misuse of human free will.64

Although Chrysostom is similar to Xunzi and Augustine in stressing that children display bad tendencies, his assessments of these tendencies are different. In comparison with Xunzi, who attributes these bad tendencies to a bad human nature, Chrysostom explicitly denies that bad behaviors can be traced back to human nature, for that would imply that human beings act badly out of necessity and therefore should not be held responsible. Chrysostom insists that “[a human person] cannot turn to his nature for an excuse, for all the evil comes from his choice [proairesis] and will [gnome].”65 Chrysostom also differs from Augustine, who associates the bad tendencies of children with Adam’s sin. Although Chrysostom admits that Adam’s sin weakens the free will of adults to make good moral choices, he does not make the connection between Adam’s sin and bad behaviors of children.

Now the question for Chrysostom is, if children’s bad tendencies are due neither to a bad human nature nor to Adam’s transgression, where do they come from? Chrysostom’s own remark might give us a clue: “All the passions are tyrannous in children, for as yet they have not that which is to bridle them.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Confucianism | Feng Shui |

| I Ching | Jainism |

| Karma | Shintoism |

| Sikhism | Tao Te Ching |

| Taoism | Tibetan Book of the Dead |

| Zoroastrianism |

The Tao of Physics by Fritjof Capra(2276)

Human Design by Chetan Parkyn(2072)

The Diamond Cutter by Geshe Michael Roach(2061)

Feng Shui by Stephen Skinner(1940)

The Alchemy of Sexual Energy by Mantak Chia(1860)

Tao Te Ching by Lao Tzu(1841)

365 Tao: Daily Meditations by Ming-Dao Deng(1621)

Tao Tantric Arts for Women by Minke de Vos(1599)

Sun Tzu's The Art of War by Giles Lionel Minford John Tzu Sun(1541)

Sidney Sheldon (1982) Master Of The Game by Sidney Sheldon(1520)

Buddhism 101 by Arnie Kozak(1512)

Karma-Yoga and Bhakti-Yoga by Swami Vivekananda(1495)

The Analects of Confucius by Burton Watson(1436)

The Art of War Other Classics of Eastern Philosophy by Sun Tzu Lao-Tzu Confucius Mencius(1428)

Tao te ching by Lao Tzu(1366)

The Way of Chuang Tzu by Thomas Merton(1365)

The New Bohemians Handbook by Justina Blakeney(1355)

The Sayings Of by Confucius(1316)

Bless This House by Donna Henes(1271)